A Cubist Critique of Photographic Art

February 21, 2012Olga Rozanova, the early 20th century Russian avant-garde cubist painter discussed the process of making art, as compared to merely copying what one sees in nature, in the journal of the Union of Youth in 1913. Rozanova states that an artist whose works are nothing more than an “unconscious plagiarism of nature,” if only due to the artist “not knowing his own objectives,” for which the artist may be forgiven, must nevertheless be rejected, and the failure to reject such works amounts to “a plagiarism in the literal sense of the word, when people refuse to reject [such artworks] merely out of creative impotence.”

According the Rozanova, the artist must be more than a passive imitator of nature. Rather, the artist must be “an active spokesman of his relationship with [nature].”

How can one do this? According to Rozanova, “a servile repetition of nature’s models can never express all [of nature’s] fullness.” And so, in 1913, Rozanova declared that “it is time, at long last, to acknowledge this and to declare frankly, once and for all, that other ways, other methods of expressing the World are needed.”

Rozanova faults photographers, who, like the servile artists, “in depicting nature’s images, will repeat them.” She contrasts such plagiarists with one of “artistic individuality”, who, in depicting nature’s images, “will reflect himself.”

Might the same criticism be leveled against the popular photographic art of today? Today’s photographic artist must be careful not to fall into the trap of the “artist of the Past,” decried by Rozanova, who, “riveted to nature, forgot about the picture as an important phenomenon, [and] as a result, [the picture] became a pale reminder of what he saw, a boring assemblage of ready-made, indivisible images of nature, the fruit of logic with its immutable, nonaesthetic characteristics.” In a word, “Nature enslaved the artist.”

For Rozanova, the then burgeoning modern art was no longer “a copy of concrete objects; it has set itself on a different plane, it has upturned completely the conception of Art that existed hitherto.”

Rozanova’s prescription for creating works of art that are not mere plagiarized repetitions of nature is, “not only by not copying nature, but also by subordinating the primitive conception of it to conceptions complicated by all the psychology of modern creative thought: what the artist sees + what he knows + what he remembers, etc. In putting paint onto canvas, he further subjects the result of this consciousness to a constructive processing that, strictly speaking, is the most important thing in Art — and the very conception of the Picture and of its self-sufficient value can arise only on this condition.”

For the photographic artist, this constructive processing must inform the editing process as one reviews the various images captured in camera.

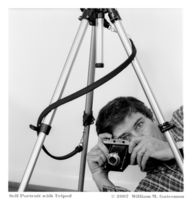

The image set forth above, Pete Plays the Blues, is far from a mere repetition of the image I saw in my viewfinder, and yet, it is the image that was captured on film. Some may have discarded this picture because it does not look like the subject framed in the viewfinder at the time the shutter was released. But to me, this image challenged me by revealing, in the Rozanova’s words, “the properties of the World,” from which I could “erect . . . a New World — the World of the Picture, and by renouncing repetition of the visible” I was able to create a different image that I was “forced to reckon with.”

How will the viewer respond to such a photograph? Rozanova observes that, “[f]or the majority of the public nurtured by pseudo artists on copies of nature, the conception of beauty rests on the terms ‘Familiar’ and ‘Intelligible.’ So when an art created on new principles forces the public to awaken from its stagnant, sleepy attitudes crystallized once and for all, the transition to a different state incites protest and hostility since the public is unprepared for it.”

By that measure, both Pete Plays the Blues, and the photo, On the Dressing Table, which is set forth above, might be said to have gone beyond the mere repetition of nature. In each case, upon first showing these photos to a friend and critic, he responded with protest. Indeed, it was not until I wrote this essay that that I recognized the significance of this unmanipulated photograph, which like the cubist paintings about which Rozanova wrote, shows my subject from multiple points of view all in the same frame.

Another image in which the resulting picture differs substantially from the subject I saw in my camera’s viewfinder is Boys at Play, reproduced below.

For Rozanova, and dare I say, for the photographic artist who strives to be something more than nature’s plagiarist, it is essential that one create works of art that are “self-sufficient,” that is, images that enjoy absolute “liberation . . . from the alien traits of Literature, Society, and everyday life.”

The photograph above, Maritime Abstraction, and other photographs that I hope are more than mere plagiarisms of nature, are shown in my online photo gallery at www.wmgphoto.com.

Olga Rozanova’s essay is reproduced in the book Art in Theory, 1900 — 2000, An Anthology of Changing Ideas, by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood.