November 14, 2007

On November 11, I wrote an article on Depth of Field in a Digital World and illustrated the post with two photographs. One of those photos, Renaissance Acrobat is a color image of a young woman in a ring suspended in midair. I was working on that picture to submit it to the Maryland Renaissance Festival 2007 photo contest, not because I thought that the photo was a particularly moving image, but because I thought it was a good fit for one of their categories. I have not, however, posted the image to my online Photo Gallery.

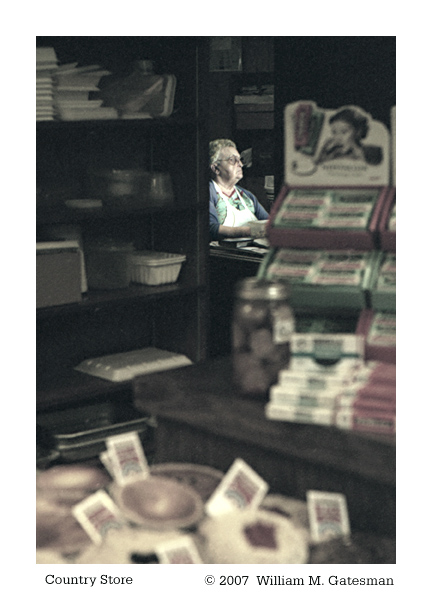

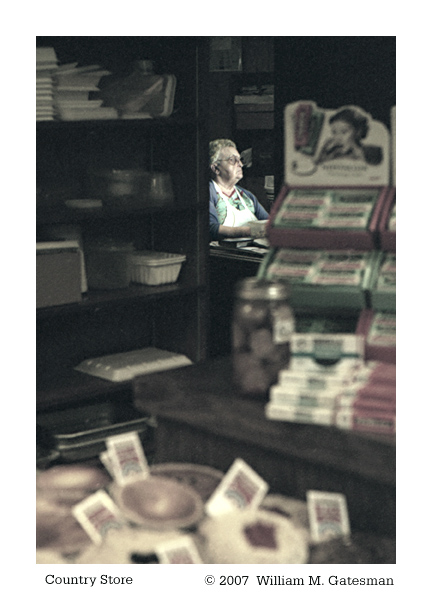

The reason I used Renaissance Acrobat in the article is that it served to illustrate my point about the limitations of digital cameras with respect to one’s ability to create an image with a short depth of field. I find Country Store, the other image in that article to be a much more compelling photograph.

I write this post because I am ambivalent about Renaissance Acrobat. I strive to show only my best work on this website and in my online Photo Gallery. I endeavor to create photographs that are emotionally compelling. I feel that Renaissance Acrobat falls short of this ideal. Nevertheless, I will retain the Renaissance Acrobat image on the overflow page of the post as an example of the point I was making.

November 11, 2007

One may surmise by looking at my Photo Gallery that I pay close attention to depth of field when taking photographs. Depth of field is the technical phenomenon that causes some parts of a photograph to be in focus and some to be out of focus. Depth of field traditionally has been caused by the relationship of the lens aperture (the size of the hole that lets light into the camera) and the size of the film. The larger the piece of film, the shorter the depth of field (meaning more of the image will be out of focus). That is why large format view cameras tend to produce images with a short depth of field at many aperture settings. As the film one uses gets smaller in size more of the image is in focus. Hence, 35mm cameras allow for a more in focus image than medium and large format cameras.

I took the photograph above, Country Store, with a 35mm film camera. I was able to set the film camera so that my subject, the woman in the back room, is in focus, and everything else in the foreground is out of focus. In my view, this short depth of field which empasizes certain elements of the image makes a much more interesting photograph than if everything was in focus. Country Store is featured in the Travel Portraits gallery at www.wmgphoto.com

To learn about the challenge of creating a short depth of field using a digital camera, click here ——> Read the rest…

November 9, 2007

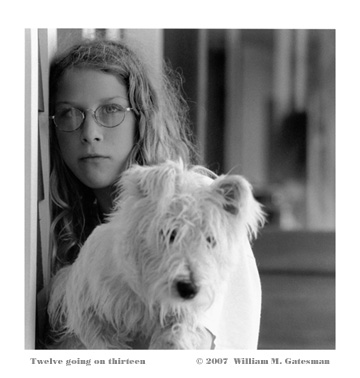

Daniel Oppenheimer, in writing about the photographer, Diane Arbus, states that her “brilliance was to catch everybody unmasked, at the moment of transition between unconscious repose and practiced, social self-representation. People seemed to reveal, in that moment, their essential being . . .”

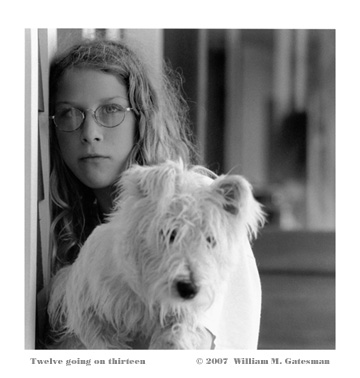

My objective in making photographic portraits is to do the same thing, although more often than not it happens by chance when I simply am taking someone’s picture. I think I have been successful in capturing my subject in that “moment of transition” in the photograph, Twelve going on thirteen.

I think that such “moment of transition” as it is represented in this photograph is a good metaphor for a budding young woman’s emotional state as she transitions from the state of being a child to the state of being a teenager. I invite you to consider also whether the background in the photograph contributes to that sense of meaning.

Twelve going on thirteen is featured in the Portraits gallery at www.wmgphoto.com

David Oppenheimer’s biography of Diane Arbus is located — Here —

November 1, 2007

Paul Indigo, in his blog Beyond the Obvious has stated that: “If you look at the great masters of photography and their images, many of which have become iconic, you see that there is a distinct gap between text book perfection and what they’ve produced. Most great pictures that touch our hearts have technical flaws. . . . But it doesn’t matter because there’s so much emotion and power in their images.”

The image in this post, Boys at Play, is a scan of a black and white photograph I created in a traditional wet darkroom. The negative for this image contains much more visual information than the print, however I used an Ilford Mutigrade filter on my enlarger which had the effect of creating the more posterized image you see here. I suppose one might be able to create a similar effect using the posterize feature in photoshop, but I don’t know if that would yield the same result with this image as I obtained using traditional photo processing techniques.

The image in this post, Boys at Play, is a scan of a black and white photograph I created in a traditional wet darkroom. The negative for this image contains much more visual information than the print, however I used an Ilford Mutigrade filter on my enlarger which had the effect of creating the more posterized image you see here. I suppose one might be able to create a similar effect using the posterize feature in photoshop, but I don’t know if that would yield the same result with this image as I obtained using traditional photo processing techniques.

Given the posterized nature of this picture, one might argue that it is not a technically perfect representation of the subject. Nevertheless, for me, it is an effective photograph because, without fail, I have an intense emotional reaction every time I view Boys at Play.

The same can be said about “Robert Capa’s shots of the Normandy landing”, to give but one of the examples pointed out by Paul Indigo. Capa’s photograph of a soldier wading in the ocean towards the shore is blurry and grainy and by no means a technically perfect image, but it is one to which I have a strong emotional response. For me, this photograph successfully captures what it must have been like to be that soldier in that circumstance.

With Boys at Play my response is something akin to dread. But, being the father of two sons, I know that boys (and their dads) often engage in rough play, play that to an outside observer may appear to be something more sinister. I believe that Boys at Play is a successful image insofar as it captures the sinister-looking nature of the interaction between two boys.

You may view a larger version of Boys at Play by logging on to the Surreal Portraits Gallery at my online Photo Gallery at www.wmgphoto.com by clicking –here–

To view Paul Indigo’s blog post Great images may be techically flawed, click –here–

Robert Capa’s most famous Normandy landing photograph can be viewed –here–

________________________________________

Paul Indigo comments:

“Interesting article and I appreciate the way you share your personal feelings about Boys at Play. The emotion in the image hits you straight away and photography is after all about communication, not slavishly following a set of dogmatic rules. I suppose the idea that you and I are trying to get across can be summed up in a simple question: ‘Do you want to be the best rule follower in the world or the best visual communicator?'”